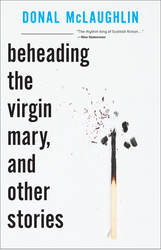

I do sometimes wonder what goes into deciding which two authors to pair up for a reading. This is especially the case when one of them, Donal McLaughlin, is a local leading light, Scottish not born but bred, and the other, Andrés Neuman, a self-professed “border citizen”, living between remote Spain and even more remote Argentina, both tackling very different topics in the book/s presented. Host and subeditor of the Guardian’s book section Richard Lea seemingly easily finds the common thread in short fiction, both in McLaughlin’s short story collection Beheading the Virgin Mary, and Other Stories (University Press Group) and the short novel Talking to OurselvesNeuman presents (luckily his first short story collection in English, The Things We Don’t Do, came out only a week ago as well, both from Pushkin Press). Throughout the discussion, the two unlikely writers turn out to have much more in common besides agreeing on many terms, making Neuman feel he has to apologize for being “so boring and agreeing with Donal again.”

Recurrent themes are identity and belonging, voice and rhythm, and translation. McLaughlin was born in Derry and moved to Glasgow at the age of nine, though elegantly circles the question whether he could be considered an Irish writer. His vernacular is a rhythmic Glaswegian with an ear for the language of the people, which he presents wonderfully in his reading of the short story ‘The Age of Reason’ about the recurrent protagonist of his collection, Liam, and his upbringing as an Irish boy in Scotland. The factual similarities between Liam and McLaughlin are evident and provoke Lea’s assertion that “it is tempting to read something of your own upbringing into Liam.” “I created Liam,” McLaughlin explains, “not to talk about me. I realised I had a special perspective on the troubles because I only ever saw them when I went over to Ireland in the summer holidays.” Besides the personal link yet with a sense of remoteness from the troubles in his native Northern Ireland, McLaughlin’s particular situation as an Irish-Scot brought with it two sets of voices: an Irish and a Scottish one. That is why, he says, he can hear the characters’ voices when writing them and “that’s what matters to me most.”

Click here to read the article at the Glasgow Review of Books